How Was the Renaissance Artist Michelangelo Inspired by Classical Art?

Beginnings of Loftier Renaissance

The Term Renaissance

It wasn't until 1855 that a French historian named Jules Michelet first coined the discussion "Renaissance" to refer to the innovative painting, compages, and sculpture in Italia from 1400-1530. His apply of the term was informed by Renaissance historian Giorgio Vasari'southward mention of "rebirth" to describe the same period in his The Lives of the Near Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (also known equally Lives of the Artists) (1568).

The term was informed past 18thursday century archeologist and art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann's The History of Ancient Art in Antiquity (also translated equally The History of Aboriginal Art) (1764) characterizing the Classical fine art of the Greeks as the "Loftier Style." Winckelmann'southward ground-breaking book launched the study of fine art history and became foundational to European intellectual life, as well equally reaching a pop audience. He felt that the purpose of art was beauty, an platonic obtained by the Greeks and in Loftier Renaissance fine art, as he wrote, "the Italians alone known how to paint and figure beauty."

By the early 1800's the term Hochenrenaissance, German for Loftier Renaissance, was used to refer to the period, defined as beginning effectually the time of Leonardo da Vinci's The Last Supper (1490's) and ending with the Sack of Rome by the army of Emperor Charles Five in 1527. In the last thirty years, some contemporary scholars have criticized the term as being an oversimplification.

The Transition from the Early Renaissance

Loftier Renaissance artists were influenced by the linear perspective, shading, and naturalistic figurative handling launched by Early Renaissance artists like Masaccio and Mantegna. But they mastered those techniques in social club to convey a new artful ideal that primarily valued dazzler. The human figure was seen as embodying the divine, and new techniques like oil painting were employed to convey human motion and psychological depth in gradations of tone and color. Drawing upon the classical Greek and Roman proportional preciseness in architecture and anatomical correctness in the trunk, masters similar Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Raphael created powerful compositions where the parts of their subjects were illustrated as harmonious and cohesive with the whole.

Leonardo da Vinci

The Loftier Renaissance began with the works of Leonardo da Vinci as his paintings, The Virgin of the Rocks (1483-1485), and, most notably, The Last Supper (1490s), exemplified psychological complexity, the utilise of perspective for dramatic focus, symbolism, and scientifically accurate item. All the same, both works were created in Milan, and it wasn't until 1500 when Leonardo moved back to Florence, the thriving center of art and civilization, that his work impacted the city. His study for The Virgin and Child with St. Anne (c. 1499-1500) was displayed at Santissimi Annunziata church where many artists went to report it.

Leonardo's scientific agreement and observation of natural phenomena and his sense of mathematical proportion were too profoundly influential. His seminal ink drawing Vitruvian Man (1490) showed ideal human being proportions correlating with ideal architectural proportions advanced past the Roman architect Vitruvius in his De architectura (30-15 BCE). The drawing is occupied by Leonardo'southward writing that illustrates his deep scientific inquiries into anatomy as, for instance, "the length of the outspread arms is equal to the superlative of a human."

Leonardo was not only a noted painter, but also a polymath who has been called the male parent of architecture, ichnology, and paleontology, among other fields. He was a noted inventor, cartographer, engineer, and his findings and observations, recorded in his notebooks, found their fashion into various collections, chosen the Codex Arundel (1480-1518) and Codex Leicester (1510), among others. To some, these notebooks have get as valued every bit his artworks.

An Age of Masters and Rivalries

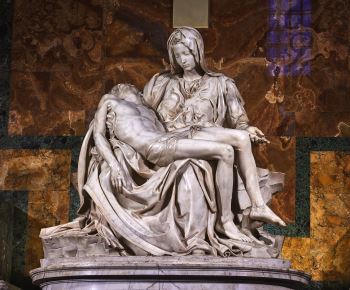

The High Renaissance was dominated by a few celebrated masters and the competitive rivalries that adult between them as they vied, not only for noble patronage, but too for supreme excellence in their fine art. In Florence, at the same time that crowds gathered to view Leonardo's cartoon for The Virgin and St. Anne (c. 1499-1500), Michelangelo had go a ascent star with his creation of the Pietà (1496-1498).

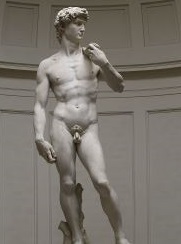

Michelangelo viewed sculpture as the pre-eminent art and, fifty-fifty in painting, sculpted the human being form. With the cosmos of the iconic statue David (1501-1504), his reputation equally the sculptor whose works exemplified the High Renaissance was established. David was given a key place in the city of Florence, upholding the city-land'south spirit of defending its civil liberties.

A rivalry developed between Michelangelo and Leonardo, beginning in 1504 with their competing frescoes commissioned for opposing walls in the Hall of Five Hundred. Equally art critic Jonathan Jones wrote of Michelangelo, "He was fiercely competitive and needed to outdo Leonardo. It became a contest non of skill, in which they were both beyond compare, but imagination and originality. Leonardo, the older artist, was already famous not just as a gifted painter only a truly original mind... [Michelangelo] set out his claim to a like kind of personal, unique vision." That personal vision can exist seen in the creative person's choice of a battle scene where nude bathers were attacked, thus allowing for a dynamic, and essentially sculptural, handling of the male nude.

The two frescos, Leonardo's The Battle of Anghiari (1503-1506), and Michelangelo's Boxing of Cascina (1504-1506), were unfortunately not completed, every bit both men were pulled toward other commissions. All the same the works continued to influence other artists, notably Raphael, who would go on to re-create the masterpieces in efforts to farther their own artistic practices.

Pope Julius Ii

Rome became the artistic eye of the High Renaissance due to the patronage of Pope Julius II, who reigned from 1503-1513. Julius II was a noted art collector, owning the Laocoon (c. 42-twenty BCE) and the Apollo Belvedere (c. 120-140), along with other noted classical works, which became the foundation for the Vatican's art museums. He was a formidable personality who made the Papacy into an economic and armed services forcefulness that dominated much of Italian republic. His goal was to make Rome the cultural center of Europe instead of Florence. To achieve this, he ardently pursued the great artists of the day, persuading Raphael to motility to Rome to pigment the frescoes of the Vatican's papal apartments. Afterwards commissioning Michelangelo to create the papal tomb. he cajoled the reluctant sculptor into painting the Sistine Chapel ceiling (1508-1512). The Pope's appetite to rebuild St. Peter'southward Basilica and redesign the Vatican led him to recruit Bramante, Michelangelo, and Raphael into roles as architects of his chiliad plans. Subsequently Julius II's death, papal patronage of the arts continued under Pope Leo Ten, the son of Lorenzo de' Medici, patriarch of the ruling (and art loving) family of Florence.

High Renaissance: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

Renaissance Man

During the Early Renaissance years, the concepts of Humanism were widely promoted. Whereas the previous Gothic menstruation'south art had emphasized the idolization of the secular and the religious, artists in fourteenth century Florence were more concerned with homo's place in the world. High Renaissance artists evolved this inquiry by exploring the concept of "universal man," in other words, an private of genius, divinely inspired, who could excel in all aspects of art and science. The term "Renaissance man" is still used today to describe a well-rounded and multi-talented person who exhibits mastery in a wide assortment of intellectual and cultural pursuits.

This ideal, adult from Leon Battista Alberti's "A human tin can do all things if he will," was exemplified in Leonardo da Vinci, as Vasari in his Lives of the Artists (1568) wrote, "In the normal course of events many men and women are born with remarkable talents; but occasionally, in a style that transcends nature, a single person is marvelously endowed by Heaven with dazzler, grace and talent in such abundance that he leaves other men far behind, all his actions seem inspired and indeed everything he does conspicuously comes from God rather than from human skill. Anybody best-selling that this was true of Leonardo da Vinci, an artist of outstanding physical beauty, who displayed infinite grace in everything that he did and who cultivated his genius then brilliantly that all issues he studied he solved with ease."

This standard non only dominated the period but subsequent thinking on artistic ability, positioning the artist as a divinely inspired genius, rather than merely a noted craftsman.

Innovations in Painting

While High Renaissance painting continued the tradition of fresco painting in connexion with religious scenes, the practice of masters like Raphael, Leonardo, and Michelangelo was informed by innovations of the medium. For example, to paint the Sistine Chapel, Michelangelo not just designed a scaffolding organization to achieve the area but developed a new formula and application for fresco to counter the problem of mold, as well as a wash technique and the apply of a variety of brushes, to first employ color so, later, add fine detail, shading, and line. For his Final Supper (1490s), Leonardo experimented by working on dry out fresco and used a combination of oil and tempera to achieve an oil painting effect. Raphael, Leonardo, and Michelangelo all employed trompe 50'oeil in their frescoes, a technique by which to achieve the illusion of a pictorial space that integrates into its surrounding architectural surround.

At the aforementioned time, many masterworks of the Loftier Renaissance were, for the first fourth dimension, existence painted in oil, typically on forest panels but sometimes on canvas. Because oils provided more possibilities in subtle tonal and color gradations, the resulting works were more life-like. Every bit a upshot, a new trunk of compelling portraiture of ordinary people emerged. Leonardo's Mona Lisa is undoubtedly the most famous example. Other High Renaissance artists like Andrea del Sarto in his Madonna of the Harpies (1517) and Fra Bartolomeo in his Portrait of Girolamo Savonarola (c. 1497-1498) also created powerful works in oil.

Leonardo'southward practice of oil painting led him to develop a new technique called Sfumato, meaning "vanished gradually like fume." It involved using translucent glazes worked by brush to create gradual transitions betwixt tones of low-cal and shadow. The result was, as Leonardo wrote, "without lines or borders, in the matter of smoke," creating a vivid imitation of reality lacking all testify of the artist's brushstrokes. Other High Renaissance artists like Raphael, Fra Bartolomeo, and Correggio also mastered the style, which later greatly influenced Renaissance painters of The Venetian School like Giorgione, and later, the Mannerist painters.

Quadratura

Quadratura was the term used for the burgeoning ceiling paintings genre of the time, remarkable for the style they unified with the surrounding architecture, and known for their employment of trompe l'oeil. These works not only included the seamless integration between painting and location, but also oftentimes required the creation of fictive architectural features to visually reconfigure the site. The employ of quadratura was used often in Cosmic churches to produce an awe-inspiring consequence, which was in straight opposition to the movement toward Protestantism that would later become the Reformation.

Quadratura required visual-spatial skill and a masterful employment of linear perspective that had first been pioneered by Andrea Mantegna in his Camera degli Sposi (1465-1474) ceiling in the Ducal Palace of Mantua. His work notably influenced Antonio Allegri da Correggio, known just as Correggio, the leader of the High Renaissance in Parma.

Correggio's ceiling frescos, Vision of St. John the Evangelist on Patmos (1520-1521) and Assumption of the Virgin (1524-30), further developed the illusionary furnishings of quadratura through his use of new revolutionary techniques like the foreshortening of bodies and objects so that they appeared authentic when seen from below. This method, likewise known as prospettiva melozziana, or "Melozzo's perspective," was adult by Melozzo da Forlì, an Italian artist and builder.

Architecture

The leading architect of the Loftier Renaissance was Donato Bramante, almost noted for his emphasis on classical harmony, employment of a central program, and rotational symmetry, every bit seen in his Tempietto (1502). Rotational symmetry involved the use of octagons, circles, or squares, so that a building retained the same shape from multiple points of view. He too created the starting time trompe l'oeil effect for architectural purposes at the church of Santa Maria presso San Satiro in Milan. Due to the presence of a road behind the wall of the church, only three feet remained for the choir surface area, and so the architect used linear perspective and painting to create an illusionary sense of expanded space.

Bramante's pupil Antonio da Sangallo the Younger designed the Palazzo Farnese which was called by Sir Barister Fletcher, "The near imposing Italian palace of the xvithursday century." The design adhered to classical principles, had a Spartan simplicity, and used rustication, which left the building stone in its textured and unfinished land allowing for natural lines and colour. The era, however, was marked by competing designs and personal rivalries. Central Farnese who became Pope Paul III in 1534 was dissatisfied with the cornice pattern of the Palazzo and held a competition for a new pattern, which was awarded to Michelangelo. The popular story recounts how Sangallo the Younger died of shame the following year, as Michelangelo completed the building's concluding touches.

Michelangelo was Bramante's principal rival, as, in later life, he worked equally an architect. He designed the Laurentian Library in Florence and created the dome for St. Peter'southward Basilica, though the building equally a whole reflected the piece of work of Bramante, Raphael, and afterward architects like Bernini. This work, which took place between 1523-1571, was specially innovative; creating a dynamic sense of movement in the staircase and wall features that was influential upon subsequently architects.

Sculpture

The undoubted principal of sculpture during the High Renaissance was Michelangelo whose Pietà, (1498-1499), finished when he was only twenty-four, launched his career. He chose to depict an unusually youthful Virgin Mary holding the dead Christ in her lap. Although the treatment of this scene was popular in France, information technology was entirely new to Italian art. The piece of work's pyramidal composition and naturalistic figurative treatment created a powerfully classical effect. Nevertheless, the work also showed innovative variations. The monumental calibration of the Virgin in comparison to Christ lent a highly emotional maternal aspect to the piece and became a signature method for the artist in his piece of work, this manipulation of high dissimilarity. Unlike Early Renaissance sculptors similar Donatello who worked in bronze, Michelangelo single handedly revived the classical apply of marble, and injected elements of monumentality into all of his subsequent sculptures, both in the size of the figures, and the scale of the projects.

Leonardo also explored sculpture, notably designing the world'south largest statuary equestrian statue. Commissioned by the Knuckles of Milan in 1482 to accolade his father, the project was never completed, equally the artist's 24-human foot alpine clay model was destroyed by the French regular army invasion of Milan in 1499. Several versions of the horse, based upon the artist's drawings, have been completed in mod times.

Later Developments - Afterwards High Renaissance

The ideals and humanism that informed the High Renaissance continued to inspire the world beyond Italy, albeit with notable stylistic and artistic variation. Its influence would reach into the North European Renaissance, exemplified past Albrecht Dürer, Pieter Bruegel, and others, and the Venetian Renaissance and the Venetian School of Painting, led by Giorgione and Titian and the architect Palladio. Meanwhile, Correggio's quadratura works influenced the artists Carlo Cignani, Gaurdenzio Ferrari, Il Pordenone, and had a notable impact on Baroque and Rococo treatments of domes and ceilings.

Leonardo'southward decease in 1519, followed by Raphael's death when he was only 37 years old the post-obit year, marked a lessened vibrancy of the Italian Loftier Renaissance. The sack of Rome by the armies of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V in 1527 ended the era. The brutal and terrifying outcome reduced the population of Rome from 55,000 to 10,000, and left the urban center in a state of collapse and financial ruin. The ethics of the Loftier Renaissance no longer seemed tenable to many. Michelangelo'southward Last Judgment (1536-41) a fresco in the Sistine Chapel expressed the darker emotional tenor of the following decades. In sculpture he turned to pietas and depictions of captive slaves such equally his The Atlas Slave (1530-34).

Michelangelo later approaches in expression influenced the Mannerists, including Jacopo da Pontormo, Rosso Fiorentino, Giorgio Vasari, and Francesco Salviati. His figurative treatment, specially of the male nude, influenced countless artists. Later artists of the Bizarre period, the Neoclassicists, and the avant-garde movements of the 20th century were as well widely influenced by the works of the Renaissance. For instance, Pablo Picasso drew upon Raphael in his Guernica (1937), referencing The Fire in the Borgo (1514), which depicted a woman handing her infant to those below as she leaned out of the burning building.

The works created by the artists of the Italian High Renaissance remain the most recognizable and popular works of art history. The Mona Lisa, The Last Supper, The Creation of Adam, and The Sistine Madonna, have been reproduced on countless consumer items, referenced in popular songs, Goggle box shows, videos, and frequently used in advertizement.

Furthermore, the ideas of the Loftier Renaissance - the artist equally genius, the foundational nature of classical art, the individual as heart of the universe, the value of science and exploration, the accent on Humanism - have all deeply informed the social and cultural values of the world ever since.

Source: https://www.theartstory.org/movement/high-renaissance/history-and-concepts/

0 Response to "How Was the Renaissance Artist Michelangelo Inspired by Classical Art?"

Post a Comment